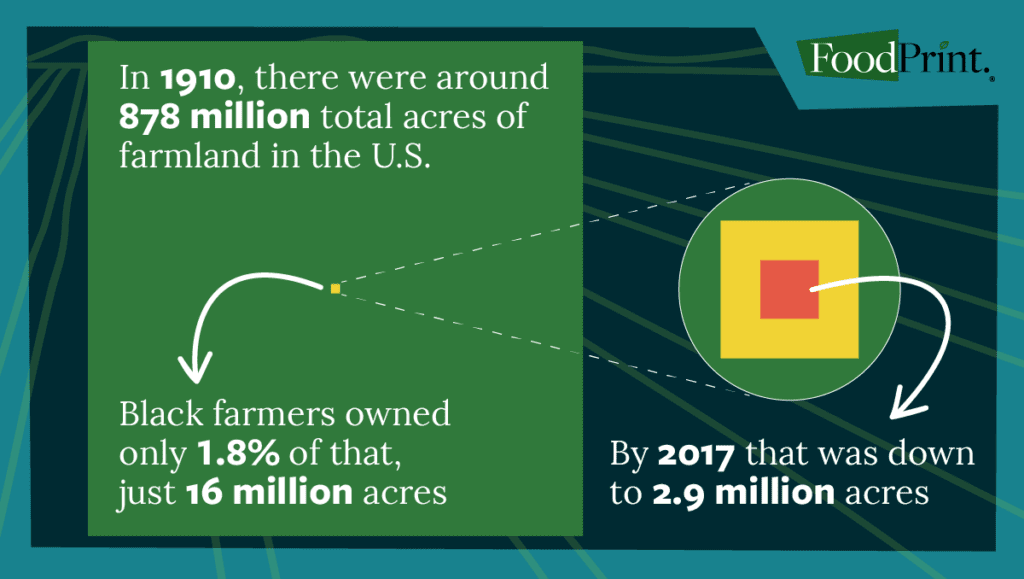

In 1910, Black farmers owned as many as 16 million acres of farmland in the United States. While that comprised only 1.8 percent of U.S. farmland at the time, Black farmers own even less today: as of 2017, just 2.9 million acres, or 0.32 percent. 12

Racist violence, anti-Black legislation, discrimination at federal agencies and other systemic injustices all contributed to that decline over the course of the 20th century. While the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s exposed some of the racism directed toward Black farmers and prompted calls for change, discrimination is an ongoing problem in the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other agencies that administer farm policy. In a farm economy where loans, credit programs and subsidies are necessary for survival, that exclusion put many Black farmers far behind their white counterparts financially, often forcing farms to close. Today, many Black farmers who have managed to hold on have limited resources to challenge discrimination or take other steps to protect their property for themselves and future generations, a problem made worse by developers who exploit legal loopholes in inheritance law to scoop up Black-owned farmland at low rates.

Black land loss represents a systemic blockage of Black Americans’ opportunity to build generational wealth: One estimate suggests that the total active farmland lost since 1920 has meant more than $326 billion in lost wealth for Black farmers and their families. 3 As farmland around the country continues to pass into a smaller number of hands, a trend of consolidation that began in the early 20th century, it’s unlikely that these losses can be reversed. But with policy changes and targeted outreach, the drivers of further land loss can be halted. Meanwhile, corrective measures for historic discrimination, while politically difficult, present an opportunity to keep Black-owned farms afloat and provide some compensation to families whose land was taken from them.

The fight for Black land ownership in the U.S.

Black people have shaped agriculture since the earliest years of European settlement in North America, with Spanish colonists bringing enslaved Africans to present-day Florida as early as 1565. 4 The first enslaved people in the 13 colonies arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, where they were forced to work in tobacco fields. 5

Between the American Revolution and the Civil War, the labor of enslaved people became central to U.S. agriculture — especially in the South, where enslaved people made up the majority of the labor force for cash crops like cotton. After Emancipation, recognizing both the skill that Black farmers already possessed and the importance of land ownership for building wealth, many Black leaders and abolitionists proposed land redistribution programs for newly freed Black people. While some early efforts — notably the Union Army’s promise to give each Black family 40 acres (and later mules) — were implemented to various extents, they were quickly reversed by President Andrew Johnson as part of his more limited plans for Reconstruction. 6

In the absence of government-administered land redistribution, many Black farmers entered into often-imbalanced agreements with white landowners as sharecroppers or tenant farmers. Sharecroppers were loaned a small portion of land and given tools, seeds and other supplies, which they then paid back with a portion of the crop, keeping the rest. Tenant farmers, who generally paid cash to rent land and purchased seeds and tools themselves, were slightly better off, with a little more control over their farms and finances.

- Sharecropper

- A farmer who loans supplies and a small portion of land from a landowner, whom they are expected to pay back with a portion of the crop — often becoming caught in a cycle of debt. For Black sharecroppers after the Civil War, the exploitative arrangement looked a lot like slavery under a different name.

But in both scenarios, the tenancy agreements were exploitative: Though chattel slavery had been abolished, white landowners still had a reliable flow of Black farm labor, and they could still make arbitrary rules about how their tenants were allowed to live. These arrangements also kept many farmers in debt, as rent for a piece of land was often higher than a realistic profit for the crops grown on it, leaving many sharecroppers in debt and unable to escape. In an effort to make as much money as possible, most relied on cash crops like cotton, which provided some financial returns but also depleted the soil over time, making each successive harvest less productive. This entrapment is the reason many historians refer to tenant farming and sharecropping as “slavery under another name.” 7

Even with the postwar promise of mass land redistribution unfulfilled and most Black farmers stuck in exploitative tenancy agreements toward the end of the 19th century, some did manage to purchase their own land in the South, thanks in large part to help from the Black community. Black thought leaders like Booker T. Washington were pivotal in helping to establish agricultural colleges and extension services specifically for Black farmers. With better training, farmers learned how to grow more diverse crops and maximize their returns, helping them escape the push and pull of the cotton market. Eventually, some were able to purchase property. 8 Other efforts, like cooperatives organized through Black churches, helped pool resources for farmers to purchase land — though the growth of these organizations was hampered by “Black codes” that limited Black people’s ability to form their own financial organizations. 9

- Tenant farmer

- A farmer who generally pays cash to rent land and purchases seeds and tools themselves. Cycles of debt are also common in this arrangement.

A few other factors in the late 19th century helped propel more Black farmers to financial independence, especially a rise in global cotton prices that meant more farmers could afford their own land than before. 10 Meanwhile, the westward expansion of the U.S. and the theft of Native American land dramatically lowered the prices of farmland in the East; because white farmers could claim new, free land in the West under the Homestead Act, many rushed to sell their Eastern farms at low prices. While Black farmers were generally prevented from claiming the free land offered to white settlers, they were able to purchase land in the East from departing white farmers. 11

Black land ownership rose slowly but steadily between 1875, when Black farmers owned about 3 million acres of farmland, and 1910, when Black farmers owned at least 12.8 million, per the U.S. Census of Agriculture. 12 Other estimates place the historic total at 16 million acres, a discrepancy that can be explained by different definitions of ownership, gaps in records and changes to the methods of the Census and other surveys. 14

Even at this peak of Black land ownership in the U.S., farmers who owned their own land were in the minority; most Black farmers (more than 600,000 by 1920) were still sharecroppers or tenant farmers. But as agriculture became more mechanized, landowners found that farming land themselves was more profitable than hosting tenant farmers, eventually pushing many Black families out of agriculture entirely and toward cities that had industrial jobs as part of the Great Migration northward.

The drivers of Black land loss

In the early 20th century, hard-earned increases in Black land ownership were halted and reversed. New agricultural policies that took effect during the Great Depression changed the economics of farming, making most farmers reliant on loans and subsidies from the USDA. But racial discrimination from the agency and its officers made it nearly impossible for Black farmers to get the same help as their white counterparts. Without resources to challenge discrimination in court, Black farmers were left vulnerable to exploitation by predatory financial institutions and white landowners. At the same time, Black farmers also faced outright violence from mobs that drove them from their land — and inaction from a legal system that did little to protect them.

While the Civil Rights Movement helped bring attention to some of these issues, Black farmers still don’t receive fair treatment from agencies like the USDA. Additionally, a lack of access to financial-planning resources has left many Black-owned farms split between multiple heirs, leaving them vulnerable to loss through court-ordered sales and tax seizures.

Black farmers left unsupported in a changing farm economy

The beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 kicked off big changes for farming in the U.S. As farmers across the country struggled with low crop prices and resulting low earnings, policies in the New Deal (a package of economic programs designed to get the economy out of the Depression) restricted acreage for crops like cotton to cut back on an excess of supply. This raised cotton prices and helped farmers that owned land, but further displaced sharecroppers who were no longer needed, preventing them from collecting income they could use to purchase land of their own.

The New Deal also marked the expansion of loan and credit programs administered by the USDA, but these weren’t as available to Black farmers as they were to their white counterparts: Racist political parties in the South pushed to make these programs locally administered, making it easy for program administrators to deny applications from Black farmers and difficult for the farmers to fight back through legal means. 16 Because Black farmers were already having trouble competing without access to USDA loans, their farmland became a prime target for white landowners looking to expand their properties.

USDA program administrators, who often believed farmland was better off being managed by white farmers, could wait to approve USDA loans for Black farmers until after planting time, forcing them to turn to banks for private loans with high interest rates. Many Black farmers were forced into debt, leaving farms vulnerable to foreclosure and sale. In many cases, these foreclosures were the result of direct collusion between USDA agents, bankers and white farmers who sought to limit the political and economic power of Black farmers. 19 Farmers also lost land through the direct actions of the government, with both federal and local governments exercising eminent domain — the forced possession of land — to seize Black-owned farms, sometimes for public works projects that never materialized. 2123

Poor enforcement of civil rights oversight

The Civil Rights Movement brought new scrutiny to government agencies and the policies they administered, prompting calls to evaluate whether programs were being enforced fairly for people of all races. In 1965, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights determined that the USDA’s loan programs had discriminated against Black farmers, leaving them out of payouts that their white counterparts had received. 25 This is partially the product of changing political priorities between administrations: The Reagan administration dismantled the agency’s civil rights office entirely, though it was subsequently reinstated in 1996 under the Clinton administration, which began reviewing the agency’s backlog of civil rights complaints. However, it made little progress before the subsequent Bush administration allowed most of these claims to expire without investigation (a move later mirrored by the Trump administration) 32

- Heirs' property

- Property that is jointly owned by the descendants of a deceased landowner. Every future descendant also qualifies as an heir and part-owner.

Even when families have legal representation in heirs’ property cases, the number of heirs can make any decisions about the land difficult to reach. Worse still, if disagreements between heirs about selling land or unifying ownership under a new title can’t be resolved and proceed to court, they typically end in court-ordered sales simply because it takes the least time and resources for the court. This makes heirs’ property especially vulnerable to exploitative sales: If a buyer approaches any heir for their share of the land, they can trigger the loss of the entire property by forcing the partition of the land if all the heirs are not in agreement about what to do with it. This technique is increasingly deployed by wealthy property developers, who find distant heirs with no connection to the land, offer them a small amount of money, then use that sale to force the rest of the heirs to sell under threat of court partition. Because many heirs are unaware of the true value of the land, developers can dramatically undercut the market value that the same property might have under more consolidated ownership.

Some estimates suggest that up to half of the 7 million acres of Black-owned land in the South could be heirs’ property.47

Previous page photo by AntonBacksholm/Adobe Stock.

Hide References

- “Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000.” USDA Rural Business–Cooperative Service, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2003, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR194.pdf.

- “2017 Census of Agriculture: Selected Farm Characteristics by Race.” USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, United States Department of Agriculture, April 11, 2019, www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US.

- Francis, Dania V. et al. “The Contemporary Relevance of Historic Black Land Loss.” American Bar Association, January 6, 2023, www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/wealth-disparities-in-civil-rights/the-contemporary-relevance-of-historic-black-land-loss.

- Ellis, Nicquel Terry. “Forget What You Know about 1619, Historians Say. Slavery Began a Half-Century before Jamestown.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, December 16, 2019, www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/nation/2019/12/16/american-slavery-traces-roots-st-augustine-florida-not-jamestown/4205417002.

- “First Enslaved Africans Arrive in Jamestown, Setting the Stage for Slavery in North America.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, August 15, 2023, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-african-slave-ship-arrives-jamestown-colony.

- Gates, Henry Louis. “The Truth Behind ‘40 Acres and a Mule.’” PBS, 2013, www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/the-truth-behind-40-acres-and-a-mule.

- Norton, Melissa. “Sharecropping, Black Land Acquisition, and White Supremacy (1868-1900).” World Food Policy Center, Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy, June 2020, wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/north-carolina/durham-food-history/sharecropping-black-land-acquisition-and-white-supremacy-1868-1900.

- “Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000.” USDA Rural Business–Cooperative Service, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2003, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR194.pdf.

- Norton, Melissa. “Sharecropping, Black Land Acquisition, and White Supremacy (1868-1900).” World Food Policy Center, Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy, June 2020, wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/north-carolina/durham-food-history/sharecropping-black-land-acquisition-and-white-supremacy-1868-1900.

- “Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000.” USDA Rural Business–Cooperative Service, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2003, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR194.pdf.

- Norton, Melissa. “Sharecropping, Black Land Acquisition, and White Supremacy (1868-1900).” World Food Policy Center, Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy, June 2020, wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/north-carolina/durham-food-history/sharecropping-black-land-acquisition-and-white-supremacy-1868-1900.

- “United States Agriculture Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000.” USDA Rural Business–Cooperative Service, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2003, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR194.pdf.

- Norton, Melissa. “Sharecropping, Black Land Acquisition, and White Supremacy (1868-1900).” World Food Policy Center, Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy, June 2020, wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/north-carolina/durham-food-history/sharecropping-black-land-acquisition-and-white-supremacy-1868-1900.

- Francis, Dania V. et al. “Black Land Loss: 1920–1997.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol. 112, May 2022, pp. 38–42, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20221015.

- Francis, Dania V. et al. “Black Land Loss: 1920–1997.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol. 112, May 2022, pp. 38–42, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20221015.

- “Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000.” USDA Rural Business–Cooperative Service, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2003, www.rd.usda.gov/files/RR194.pdf

- Francis, Dania V. et al. “Black Land Loss: 1920–1997.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol. 112, May 2022, pp. 38–42, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20221015.

- Rosenberg, Nathan, and Stucki, Bryce Wilson. “How USDA Distorted Data to Conceal Decades of Discrimination Against Black Farmers.” The Counter, June 26, 2019, thecounterorg.wpengine.com/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights.

- “One Million Black Families in the South Have Lost Their Farms.” Equal Justice Initiative, October 11, 2019, eji.org/news/one-million-black-families-have-lost-their-farms.

- Burch, Audra D.S. “A New Front in Reparations: Seeking the Return of Lost Family Land.” The New York Times, The New York Times Company, June 8, 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/06/08/us/black-americans-family-land-reparations.html.

- Oyer, Kalyn. “New Documentary on Wealthy SC Black Cotton Farm Owner Who Was Lynched for Success.” Post and Courier, Evening Post Publishing Newspaper Group, November 17, 2020, www.postandcourier.com/charleston_scene/new-documentary-on-wealthy-sc-black-cotton-farm-owner-who-was-lynched-for-success/article_7ce0fb88-1f94-11eb-ab94-fba480869e15.html.

- Lewan, Todd and Barclay, Dolores. “Torn from the Land (Part 1 of 3).” Hartford Web Publishing, December 2, 2001, www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/393.html.

- Ibid.

- Hayes, Jared. “Timeline: Black Farmers and the USDA, 1920 to Present.” Environmental Working Group, February 1, 2021, www.ewg.org/research/timeline-black-farmers-and-usda-1920-present.

- Scott, Emma et al. “Supporting Civil Rights at USDA: Opportunities to Reform the USDA Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights.” Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School, April 2021, chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/FLPC_OASCR-Issue-Brief.pdf.

- Hayes, Jared. “Timeline: Black Farmers and the USDA, 1920 to Present.” Environmental Working Group, February 1, 2021, www.ewg.org/research/timeline-black-farmers-and-usda-1920-present.

- Rosenberg, Nathan and Stucki, Bryce Wilson. “How USDA Distorted Data to Conceal Decades of Discrimination Against Black Farmers.” The Counter, June 26, 2019, thecounterorg.wpengine.com/usda-black-farmers-discrimination-tom-vilsack-reparations-civil-rights.

- “Report of Civil Rights Complaints, Resolutions and Actions for Fiscal Year 2021.” USDA Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, United States Department of Agriculture, December 7, 2022, www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/report-civil-rights-compliants-resolutions-actions-fy-2021.pdf.

- Spiegel, Bill. “USDA: The Last Plantation.” Successful Farming, Dotdash Meredith, February 5, 2021, www.agriculture.com/news/usda-the-last-plantation.

- Pennick, Edward Jerry and Rainge, Monica. “African-American Land Tenure and Sustainable Development: Eradicating Poverty and Building Intergenerational Wealth in the Black Belt Region.” Forest Service Research and Development, United States Department of Agriculture, June 15, 2017, www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr-srs244/gtr_srs244_011.pdf.

- “Heirs’ Property Landowners.” Farmers.gov, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2023, www.farmers.gov/working-with-us/heirs-property-eligibility.

- Pennick, Edward Jerry and Rainge, Monica. “African-American Land Tenure and Sustainable Development: Eradicating Poverty and Building Intergenerational Wealth in the Black Belt Region.” Forest Service Research and Development, United States Department of Agriculture, June 15, 2017, www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr-srs244/gtr_srs244_011.pdf.

- Rothstein, Leah. “Keeping Wealth in the Family: The Role of ‘Heirs Property’ in Eroding Black Families’ Wealth.” Working Economics Blog, Economic Policy Institute, July 6, 2023, www.epi.org/blog/heirs-property.

- Pennick, Edward Jerry and Rainge, Monica. “African-American Land Tenure and Sustainable Development: Eradicating Poverty and Building Intergenerational Wealth in the Black Belt Region.” Forest Service Research and Development, United States Department of Agriculture, June 15, 2017, www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr-srs244/gtr_srs244_011.pdf.

- Bustillo, Ximena. “A USDA Commission Issues Recommendations on Racial Equity for Farmers.” NPR, February 28, 2023, www.npr.org/2023/02/28/1160065628/usda-equity-commission-report-interim.

- Joyce, Kathryn et al. “The ‘Machine That Eats up Black Farmland.’” Mother Jones, 2021, www.motherjones.com/food/2021/04/the-machine-that-eats-up-black-farmland.

- Simpson, April. “Shirley Sherrod Was Fired by USDA. Why Is She Serving the Agency Again?” The Center for Public Integrity, February 11, 2022, publicintegrity.org/inequality-poverty-opportunity/shirley-sherrod-joins-usda.

- Cowan, Tadlock and Feder, Jody. “The Pigford Cases: USDA Settlement of Discrimination Suits by Black Farmers.” National Agricultural Law Center, Congressional Research Service, May 29, 2013, nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RS20430.pdf.

- Hayes, Jared. “Timeline: Black Farmers and the USDA, 1920 to Present.” Environmental Working Group, February 1, 2021, www.ewg.org/research/timeline-black-farmers-and-usda-1920-present.

- “Pigford Payouts to Black Farmers Reach $2.3 B. – Will There Be More?” Agri-Pulse, Agri-Pulse Communications, Inc., July 9, 2014, www.agri-pulse.com/articles/4200-pigford-payouts-to-black-farmers-reach-2-3-b-will-there-be-more.

- Bustillo, Ximena. “Black Farmers Worry New Approach on ‘Race Neutral’ Lending Leaves Them in the Shadows.” NPR, February 26, 2023, www.npr.org/2023/02/26/1159281409/black-farmers-worry-new-approach-on-race-neutral-lending-leaves-them-in-the-shad.

- “Protect Your Land.” Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation, 2023, www.heirsproperty.org/protect-your-land.

- “About Us.” Land Loss Prevention Project, 2021, landloss.org/about/index.html.

- “Heirs’ Property Relending Program.” Farmers.gov, United States Department of Agriculture, October 2023, www.farmers.gov/working-with-us/heirs-property-eligibility/relending.

- “FSC/LAF 2023 Annual Report.” Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund, August 27, 2023, federation.imagerelay.com/share/c62d6b82778d437a9ba7c4a2fbb22f80.

- “Protect Your Land.” Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation, 2023, www.heirsproperty.org/protect-your-land/.

- Jones, Collis. “RE: Docket USDA-2021-0006.” Received by Tom Vilsack, Secretary, U.S. Department of Agriculture, John Deere, July 14, 2021, https://www.deere.com/assets/pdfs/common/our-company/news/deere-comment-letter-docket-usda-2021-0006.pdf.